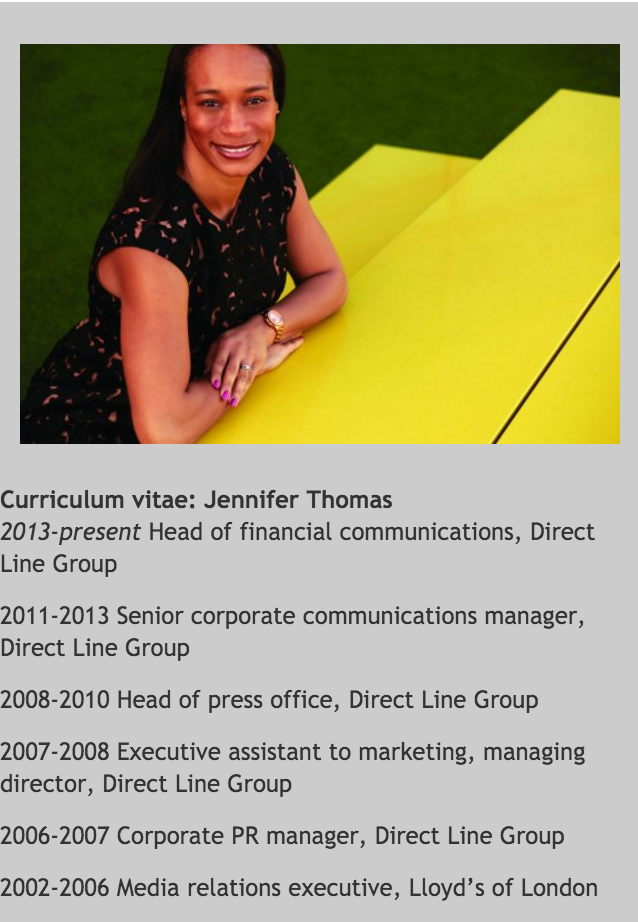

THE FINISH LINE

Accomplished sprinter and head of financial communications at Direct Line Group, Jennifer Thomas talks career progression, public relations and athletics with Andrew Thomas

Athletes seem either to be full of themselves or modestly self-effacing. “You can’t propel yourself forward by patting yourself on the back,” said American Olympian and seven- time record holding runner Steve Prefontaine. There is a similar self-deprecation in Jennifer Thomas, of FTSE 100 insurance giant Direct Line Group, when she talks of her time as a track athlete, her achievements with the Direct Line IPO and the obstacles she has overcome. The self-deprecation isn’t, however, born out of shyness but instead masks a confidence and steely focus to a career that has led her to her current role of head of financial communications.

Part of that confidence may be explained by a somewhat disjointed upbringing. Born in London, to immigrant Guyanese parents, Thomas was the youngest of two sisters separated by a 20 year age gap. Britain in the ’70s and early ’80s was a challenging place to grow up if you were a child of colour and when her sister, almost a second mother to the six year-old Thomas, married and moved to California, her parents had less reason to stay rooted in London and moved to Toronto. For the first few months, Thomas was mocked for her London accent, causing her to retreat into herself and stop talking. Instead, she watched and listened closely to her peers. As she recalls, “Moving to Canada was difficult. The mark of me overcoming that has led to who I am now. I think it’s why I’m able to adapt and fit in with any group of people.” When Thomas was ready to talk again, there was no tracing her English origins. To this day, it’s hard to pin down the genesis of her diction.

Those first few months aside, it was a happy childhood. Excelling academically, she filled the rest of her time with music lessons and dance classes, abandoning the latter when she was 13 and replacing it with athletics. Thomas spent summers with her sister in California, which became a second home to her, and when it was time to make her university choices, America won out over Canadian colleges. She majored in economics, but returned to dance, combining the two with a thesis on the economic models of performing arts and graduating with an unusual degree in dance and economics.

Those first few months aside, it was a happy childhood. Excelling academically, she filled the rest of her time with music lessons and dance classes, abandoning the latter when she was 13 and replacing it with athletics. Thomas spent summers with her sister in California, which became a second home to her, and when it was time to make her university choices, America won out over Canadian colleges. She majored in economics, but returned to dance, combining the two with a thesis on the economic models of performing arts and graduating with an unusual degree in dance and economics.

As with many courses, Thomas’ involved a third year studying abroad. She chose London, staying on for the summer as a receptionist for a tech start-up called Virtual Plus. She obviously made an impression – the owner offered her the job of office manager when she finished university. A year later Thomas started, but was called in to the MD’s office on her first day to be told the head of marketing was leaving. The MD turned to Thomas and said, “You know what we do, we want you to run marketing.” But, she says, “I knew nothing about marketing, I hadn’t done a single class or module on marketing at university. All of these doubts are going on in my head but I just said, ‘Sure, yes let’s do it,’” It was an opportunity that was to shape the rest of her career.

Unencumbered by protocols and perceptions of what would work, Thomas says her first job was the best introduction to communications, “I understood the company and I just got on with it. I had very little marketing budget and I did a lot of what I now call guerilla PR. I was allowed to learn and experiment. I was, effectively, a decision maker straight after leaving university. That experience would have taken more than 10 years to get elsewhere.”

“In most organisations, comms definitely wasn’t embedded in the business. I wanted to change that and understand the business metrics. I started pushing hard to integrate myself into the business”

Thomas was there for five years. Sadly, however, the company was unable to keep up to date with technology and two years before the firm went into administration Thomas was made redundant. “During my time at Virtual Plus, I had so much fun – too much fun – and I forgot about investing in myself. I gave no thought about what might come next,” she says. “Being made redundant was horrible, but in some ways it was the best thing that could happen to me. It meant I would not make that mistake again.” Her redundancy package was small, and, although the time off forced her to focus on her strengths and the areas of her work she enjoyed, she didn’t have much of a cushion. The area she enjoyed was PR. “Virtual Plus was a technology firm, but if you talked like a geek no one would be interested. I loved taking complex ideas and distilling them into something digestible. I loved dealing with publications and working with their news agendas. I realised that I was still learning the game, but PR was definitely the game I wanted to play,” Thomas says.

She found unemployment a scary time, but after a couple of months, Thomas landed the role of corporate PR manager for Motability, the UK’s largest car leasing firm, providing finance options for disabled drivers. It was a new role, and Thomas found it fascinating. Jointly owned by Barclays, HSBC, Lloyds and RBS, Motability had a bad reputation with the media. “The press tended to write stories about how Motability took advantage of disabled drivers rather than offering them independence. A large part of the job was about changing that mindset,” she says.

During the following year, she relaunched Motability’s comms strategy, personalising the various corporate brand touchpoints. She is uncertain, however, if she would have taken the role if she had been in work. “If I had put down the top 10 list of what I wanted, the Motability job probably had four. I took it because I needed the money. I got lucky because actually, it was really interesting. It helped me develop, but that was more by luck than judgement.”

The development wasn’t to last. Eighteen months into the role and the four banks swooped down and exercised their rights to instigate a massive cost cutting and transformation programme. There were almost 3,000 redundancies and Thomas was one of them. “It hit me hard,” she says. “I was now seven years outside of university, and I’d been made redundant twice already.”

It knocked her confidence, but running helped maintain her spirits. A keen college runner, she continued focusing on athletics when she moved to London, adding 400-metre hurdles to her forte of 100- and 200-metre sprints. Her new, enforced free time gave her extra hours to train. But it limited the jobs for which she applied. “When interviewers asked about my out-of-work activities I was quite pleased that I could talk about running,” Thomas says. “But with agencies, the interview then turned to the expectations of the hours I could work. I realised that I really didn’t want to give up my athletics and that agency life really wasn’t for me.” Thomas was out of work for six months. Anxiety was beginning to creep in, when the next job turned up, in media relations for the insurance marketplace, Lloyd’s of London.

Lloyd’s of London gave Thomas experience in understanding the way a business worked, and the importance of this to the management of its communications. “I know that sounds really obvious, but back then, you still had businesses that weren’t investing in comms or where comms sat on the sidelines,” she says. “In most organisations, comms definitely wasn’t embedded in the business. I wanted to change that and understand the business metrics. I started pushing hard to integrate myself into the business. I shadowed the strategy director, getting into the nuts and bolts of the business. That helped me build relationships with journalists – suddenly I‘m not a person who just emails press releases, but I’m now a person with whom they can actually have a business conversation.”

It was a flat structure at Lloyd’s, and four or five years after starting, it was time to think about career progression. She says, “Lloyd’s was a brilliant learning experience for me. It taught me how to be a business woman, not just a comms professional. It taught me to fight for myself as a woman, and as a black woman. I learned how to stand my ground, and believe in my own skill and expertise. It gave me the confidence to challenge and be part of the debate. I thought, that’s what I want to take with me to my next role.”

Deciding to leave was the easy part; the harder aspects were where to go and where to go with her running. She was competing at a national level and Lloyd’s accommodated her training with alacrity. Lloyd’s had given her great experience – she had revamped its internal comms strategy, ran the annual report and taken on crisis communications – but neither her job title nor her salary reflected it. She needed, and wanted, to move her career up to the next level, but she wasn’t in a hurry. Communications was becoming more integrated and Thomas wanted to wait for the right role.

Then, a corporate PR manager vacancy came up at RBS Insurance. It coincided with Thomas narrowly missing out on a place to compete with TeamGB in the Commonwealth Games. Thomas went for the job, deciding that if she didn’t get it, she would put her career on hold and commit to training for an Olympic place. Equally, if she got the job she’d give up athletics. She got the job and made the hard decision to give up running.

RBS Insurance was later to become Direct Line Group, but from day one, Thomas realised she’d made a mistake. There was no corporate PR at RBS Insurance, as corporate was handled at the RBS group level. She felt she’d given up her running for a job that didn’t exist. Over the next two months, Thomas hunted down challenges and set herself the task, realised over the following year, of creating a crisis communications plan and media training programme.

Fortunately for Thomas, the culmination of the crisis planning coincided with the appointment of a new communications director who created a new comms structure with two press offices, one on proactive media relations, the other on reactive PR. The work Thomas had been doing in crisis comms made her an obvious candidate for the head of press office working on the reactive comms.

This was 2008, and as RBS had been a major recipient of bail-out funds following the banking collapse, the media was giving it a hard time. As economic recovery started, the government was keen to sell the insurance arm of RBS, and Thomas was promoted to senior corporate communications manager on the run up to the IPO that Direct Line Group orchestrated. The IPO was the biggest stock market listing of 2012, and Thomas’ team won ‘Best Financial and Investor Relations Campaign of the Year’ at the following Chartered Institute of Public Relations’ annual awards. In 2013, Thomas was promoted to head of financial communications. Her remit is external communications, but she works closely with other comms teams, all of which have different reporting lines. “It’s a unique structure, and it requires us all to talk and support each other,” she says.

It is, however, a structure that doesn’t currently offer promotion. “My next role would need to be a directorship, running all the areas of communications, and the current structure doesn’t really allow for that,” says Thomas, adding that the advice she gives people is to think of the five year trajectory. “I think it’s important to work backwards from what you want to be, even if those steps don’t automatically lead to promotion. My attitude has been that whatever I am doing has to be a CV builder.” Fortunately for Thomas, Direct Line has consistently provided new opportunities. She says, “There have been various points when I’ve questioned staying. Before the IPO came up, I was thinking it was time to go, but then I thought, ‘Ooh, I want to be part of that.’ Then after the IPO, I was promoted again. It’s 10 years next year, and I’m still driven. Which is good.”

It’s clear that sport has helped Thomas’ drive. She’s a competitive person, but also feels strongly that the playing field isn’t level. She plays an active part in tackling the wider issues of diversity and inclusion, “We need to explore and break the social norms, and allow our children to be whatever they want to be. We need to challenge the unconscious bias the exists in our society. We are drawn to people who look and sound like us, but if you don’t see any investment bankers from your background you’re less likely to enter that profession and we need to explore ways to change that.”

Thomas doesn’t run anymore, “I am too competitive, and running without that element wasn’t enough for me. Going onto the track now seems pointless, I don’t really know what I would be trying to achieve. I need something to drive me.” For the moment that something is Direct Line, but it’s clear there are a number of races still left to run.

Photographs by Jeff Leyshon