NOT WHAT THE FUTURE USED TO BE

Not what the future used to be: As financial services reemerges from the recession, banks have to win back trust, reinvest in their brands and redetermine their place in society. David Benady investigates.

"World, here I come” is the latest advertising slogan used by Dutch bank ING as it emerges from the dark days of the 2008 banking crash and seeks to transform perceptions of its values and ambitions.

ING has plastered Amsterdam’s Schiphol airport with posters featuring variations on the theme such as: “Madrid, Here I come,” “Uncharted territory, Here I come” and “Mum’s cooking, Here I come.

”Attempts to cast ING in a more optimistic, helpful light reflect a wider move by financial brands to repair their battered reputations in the aftermath of the financial crisis.

Like many of the world’s biggest banks, ING faced collapse during the crash. It was forced to accept a $10bn state bailout and divest all its non-banking activities such as insurance and car leasing. Now, with new chief executive Ralph Hamers at the helm and a turn-around strategy called Think Forward, ING is looking to transform people’s understanding of what banks are for.

“The campaign is about people doing what is important for them, but with us helping and facilitating and empowering them,” says Nanne Bos, ING’s head of global brand management.

Where previously banks made bold, hubristic statements about the benefits of size and how they could make people richer, today they are redefining themselves as enablers, supporting people’s choices. “You won’t see anything about us in the campaign, we are not saying how global we are, how many markets we are in nor what you should do with your money,” says Bos. Instead, the campaign, created by agency United State of Fans/TBWA, seeks to show how banks can give people confidence, “To pursue their ambitions however big or small,” according to Bos.

Bos is overseeing a wider rebranding exercise for ING, after chief executive Hamers’ identified the brand as one of the bank’s most valuable assets. Persuading staff and senior managers to buy into the brand positioning has been a vital part of the task. “It took some time to get people to open up their minds to the future rather than being stuck in their own context and business units. What are you part of, the business unit or the bigger story going forward?” says Bos.

But there is a thin line between humility and appearing apologetic. Striking the right note in relaunch advertising and brand campaigns requires great sensitivity. RBS and its NatWest subsidiary – which received a £46bn state bailout in the UK and are still Government-controlled – relaunched using the advertising line, “Goodbye unfair banking, hello NatWest” (“hello RBS” in Scotland). Did this serve as an apology for their own poor showing or was it an acknowledgement that the whole banking system was unfair? Was it too apologetic or did it show the right level of humility?

Lloyds spun off its TSB division into a separate bank using the slogan, “Welcome back to local banking,” But some wonder whether the bank has done too little to acknowledge its own failings and contribution to the crisis.Banks across Europe and the US are facing similarly tough questions as they pursue relaunch strategies. New banking regulations are in place to try and ensure that there is no repeat of the crisis.

The institutions insist they have cleaned up their acts and many have paid a high price, not just in fines. Barclays closed down its wealth management arm – worth £1bn a year in profits – after incoming chief executive Antony Jenkins put ethics before profit and judged that the division was little more than a tax dodging operation.

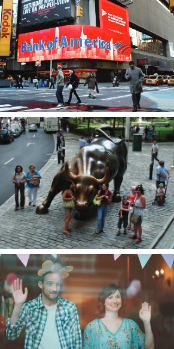

As 2008 recedes into memory, attempts are emerging to make banking seem nicer, more human-scale and less greed-driven. But there are constant reminders about the misdemeanours of the sector with fresh scandals still ongoing. The name HSBC regularly crops up in scandals while Barclays has been at the centre of repeated misconduct allegations. In 2014, six years after the crash, memories of that dark era were stirred up again when Bank of America (BofA) was handed the biggest ever corporate fine – nearly $17bn – for the misdemeanours of the two financial brands that it bought during the crisis, Countrywide Financial and Merrill Lynch.

Bank of America stepped in to buy Merrill Lynch at the height of the crisis as the brokerage faced collapse. It was a controversial deal as BofA paid $50bn and some argue that price tag could have been lower had it waited just a few days longer. The US government bailed out BofA with $20bn to pay for Merrill Lynch’s losses.

Thus, the task of creating a set of coherent messages about the unified Bank of America and Merrill Lynch after the acquisition was a significant challenge.Branding agency Brand Union worked on the relaunch, moving the brand away from the aggressive and muscular image it had espoused in the past and attempting to give it a softer and more socially-constructive feel.

Merrill Lynch’s iconic bull logo was the first thing to go. The bull statue was introduced in 1974, but was felt to be an overly aggressive symbol for a new era in which banks are trying to avoid appearing hard-edged and greedy. The symbol was phased out, though still appears in some of Merrill Lynch’s divisions, such as the wealth management arm Merrill Edge.

Veb Anand executive director of strategy for Brand Union New York, says that in 2013, the agency helped BofA put in place an integration of the entire enterprise, repositioning it “For the human era.” Rather than focusing on growth and the opportunities in risk-taking, the bank adopted a new narrative about connectedness, using the line, “Life is better when we are connected.” The rebrand included a new brand identity for the three divisions of wealth management, corporate and global. There was a global product campaign and an employee engagement plan.

“Banks had been large edifices using powerful, hard-edged symbols, scale, stability and their global footprint. In the US, all of that had to suddenly change, they didn’t have the credibility to position themselves like that,” says Anand. “Everyone wanted more humanity and transparency, putting on a more human face because people didn’t understand what banks did to make so much money. The banks have tried to make it seem like something more tangible, the narratives became more about explaining to people.

”Brand Union also worked on rebranding HSBC. Anand says the decision to axe the “World’s local bank” positioning was taken because it no longer fit with the socially-responsible approach required of banks post- 2008. The line had initially been intended to show how the bank understood people’s differences and used that knowledge globally. However, it ended up being a statement of scale, power and ubiquity.

“Financial institutions started to rethink their narratives, to explain why they were important in keeping economies running, lending to small businesses and managing growth, that they weren’t in it for themselves and that it was a viable business model,” says Anand.

Financial institutions started to rethink their narratives, to explain why they keep economies running

Politicians in the UK have hailed a return to so-called ‘traditional banking,’ in which local managers have direct relationships with local businesses, as a solution to the excesses of the past.

But banking seems in reality to be going in the other direction, focusing more on online and mobile banking as people seek to keep their relationships with the banks at arms length. This is a problem for those banks with huge retail estates, as in the United States.

As Arthur Gilmore, founder of design and branding agency Gilmore Group, says, “One of the biggest challenges in the US is getting people to go to the banks. They have a lot of real estate and are trying to make that into a purpose-driven relationship so customers want to go to get advice on how to deal with their financial needs.

”He says a lot of banks in the US are still like the ones you see in old cowboy movies, “With tellers, a couple of desks and a safe at the back; they haven’t changed much.” He believes the banks of the future will be selling cars and homes. “How do you make people want to spend more time there? A bank needs to be a lot more than it has been for the past 200 years,” he says. But he adds that it is a struggle to get US banks to accept that they need to transform their approach to banking and use their extensive retail estate for wider purposes.

In the UK and Europe, many banks have drastically shrunk down their estates, instead concentrating on communicating with customers through technology. But it is clear that part of reframing the idea of banking will require a more human face and a more direct relationships with customers – especially business customers – through branches. Simply creating a new brand or ad campaign is not enough to restore trust. The proof will be in the experience people have with their banks and whether these institutions have safeguarded themselves from future crises. As Nanne Bos from ING says, “You can’t regain trust with a campaign. You have to give it before you get it.”