21ST CENTURY SPACE RACE

Space exploration is intrinsically tied to communications. Have technological and communications advancements paved the way for a modern day space race? Brittany Golob investigates

The Richard Nixon Presidential Library says that 600m people tuned in live on 20 July, 1969 to watch three astronauts in a lunar lander become the first human beings to set foot on another celestial body. From the earliest recorded chapters of history, humans have looked to the skies for navigation, meaning, wonder, doom, exploration and imagination. Only in this most recent era – the Space Age – have people been able to travel the 100km above the Earth’s surface and touch the infinite.

The Richard Nixon Presidential Library says that 600m people tuned in live on 20 July, 1969 to watch three astronauts in a lunar lander become the first human beings to set foot on another celestial body. From the earliest recorded chapters of history, humans have looked to the skies for navigation, meaning, wonder, doom, exploration and imagination. Only in this most recent era – the Space Age – have people been able to travel the 100km above the Earth’s surface and touch the infinite.

The Apollo 11 mission was NASA’s crowning achievement of the space race – the drive to conquer the strategic corner of the Cold War that was space – but the modern space race is all about communications. Scientists, public agencies, academics and private companies are all looking for a piece of the funding, support and interest provided by national and regional governments to space exploration. The race for the brand of space is still on.

Lewis Dartnell, astrobiologist, author and UK Space Agency research fellow, does outreach around public knowledge and interest in space. He says, “The UK Space Agency and ESA have a social responsibility because they’re indirectly funded from tax money. If you’re taking money from the populace via taxes you have to explain to that populace what it is that you’re doing with your money. A more important point is, people understand that education is important and getting correct information out there is important and getting people interested in what you’re trying to do is important. From a superficial point of view, if you can excite people by what you’re doing and they’re interested in what you’re doing then you’ll have an easier political time of it because you know you have the support of the population.”

The biggest stakeholder group in public space exploration is just that – the public. Even in military missions and research, the taxpayer’s interests must be kept in mind. But that becomes challenging as missions become more complex, as space endeavours have to compete on social media with other visual and scientific content and as budgets grow tighter. It could be tempting for governments to shrink aerospace budgets as the direct return on investment for space exploration is not always apparent.

Communications in this sector must educate the public about the return on investment achievable in aerospace, improve awareness and excitement for space exploration and encourage governments and private companies to support the $706bn global industry. There is always a return on investment, those in the industry say. However, it’s often in the form of spin-off technologies and programmes have made everything from phone calls to detecting skin cancer to the steel industry’s efficiency to firefighting communications better. This is the primary focus of aerospace agencies say communicators from NASA and the UK Space Agency (UKSA).

VP of communications at Lockheed Martin’s Space Systems Company Andrea Greenan, says, “A lot of the technology spin-offs provide so much value that when you start to talk about look at what earlier exploration has delivered in terms of communications, medical advances, technologies; that people understand. When we are pursuing this exploration, of course our goal [in the Orion programme – see page 16] is to reach Mars, but what else are we going to discover along the way? I’m not talking just scientific exploration, but are we going to find ways that we can better store and prepare food, to clean water, to help humans survive long periods of time and exploration modes. I think all of those provide benefits that people don’t always necessarily align with this kind of work.”

NASA’s remit goes beyond exploration. But both Bob Jacobs, deputy associate administrator for communications at NASA and Julia Short, press officer for the UKSA, say exploration is what sells. Pictures of Mars rovers or the Hubble Space Telescope’s stunning supernovae make the headlines, but the remit of both agencies includes the strategic technologies that keep modern life running. Jacobs says, “NASA does all that for less than .5% of the federal budget. Any smart investor puts aside a small amount of money on high-risk, high-return investments. I think we make those investments smartly and deliver great return on that .5%.”

Short adds, “Yes, space exploration is expensive but the UK doesn’t do it alone. We are able to play a role in some of the world’s biggest space missions by investing in the European Space Agency (ESA) and collaborating with other nations. For every pound invested by the UK Space Agency in ESA there is a return to the UK economy of about £7. Also, most of the exploration missions we invest in have many spinout benefits and applications meaning that it isn’t such a hard sell.” She adds that aerospace contributes £11.8bn to the UK economy each year at a 7% growth rate. EU growth outpaces American economic success in the sector, according to a Deloitte study.

Faye Hunter, project manager for ESA’s Mars rover mission at Airbus Defense and Space, said on Radio 4’s ‘The Long View’ on 15 September, “It’s very important to have pictures not just for raising [the media’s] interest but also for inspiring the next generation of scientists and engineers to consider working in this kind of industry as well. We’re going to have a skills shortage and a gap and it’s very important to inspire young people to fill the gap for us so we can maintain these sort of missions.”Another aspect of the investment in aerospace is employment. For years, aerospace represented the holy grail of engineering jobs, but, an estimated 40% of the aerospace workforce is due to retire in the next few years. This so-called Apollo generation was inspired by the Apollo missions of the early 1970s. Greenan says encouraging students into science and engineering now will help secure the future pipeline of talent. She says, “Parents are posting pictures of their five year-old who is dressed as an astronaut at Halloween because of the science. These are audiences that I may not be trying to reach to essentially sell the programme, but I need those folks to be excited about space exploration because they are the next generation of astronauts, they are the next generation of explorers. If someone sets foot on Mars, it’ll be the five year-old who dressed up as an astronaut on Halloween this year.”

|

Shooting for Orion

“A big part of it was to reengage the American public,” Allison Rakes, lead communicator for Orion and public relations officer, says. “A lot of people thought that since the retirement of the shuttle programme, NASA wasn’t involved in human spaceflight anymore. We wanted to help NASA change that perception here in the United States.” She adds that support for a mission such as Orion has a variety of possible returns on investment aside from bolstering human knowledge including but not limited to scientific discovery and technological advancement. Andrea Greenan, VP of communications at Lockheed Martin’s Space Systems Company, says pop culture interest in Mars has helped too. But the team primarily focused on media relations and digital in the run- up to EFT-1’s launch. “The digital and social media was important because it helped us reach audiences that we normally wouldn’t be able to reach,” Greenan says. The 60-plus comms team targeted Millennials and schoolchildren to encourage education about space exploration. They even put a dinosaur tooth on board the test rocket combining two of kids’ perennial favourite topics: dinosaurs and astronauts. “We tried a lot of different things in order to get through to people. We got proactive and aggressive with pitching our Lockheed Martin executives to the media,” Rakes adds. They also created animations and infographics to explain the mission and launched a social campaign called #MarsWalk. It encouraged users to post videos of themselves doing the moon walk variant. This yielded over 6m impressions on Twitter, part of the overall 5bn for the campaign. They also put cameras on board to stream live action back from the test flight. The goal was to humanise the unmanned test flight and help people understand what a manned mission to Mars would entail, scientifically and logistically. Internally, the campaign was a highlight of Lockheed Martin’s intranet. The successful launch led to a room full of reporters giving NASA and Lockheed Martin executives a standing ovation at a press conference, a record-smashing social media campaign and President Barack Obama using Lockheed Martin’s own messaging in his congratulatory message. Rakes says Orion is inspiring, a huge driver for space communications. It’s the logical next step from Apollo, the lunar landings, the International Space Station, Hubble and everything in between. “Mars is something that this next generation can own as their NASA mission.” |

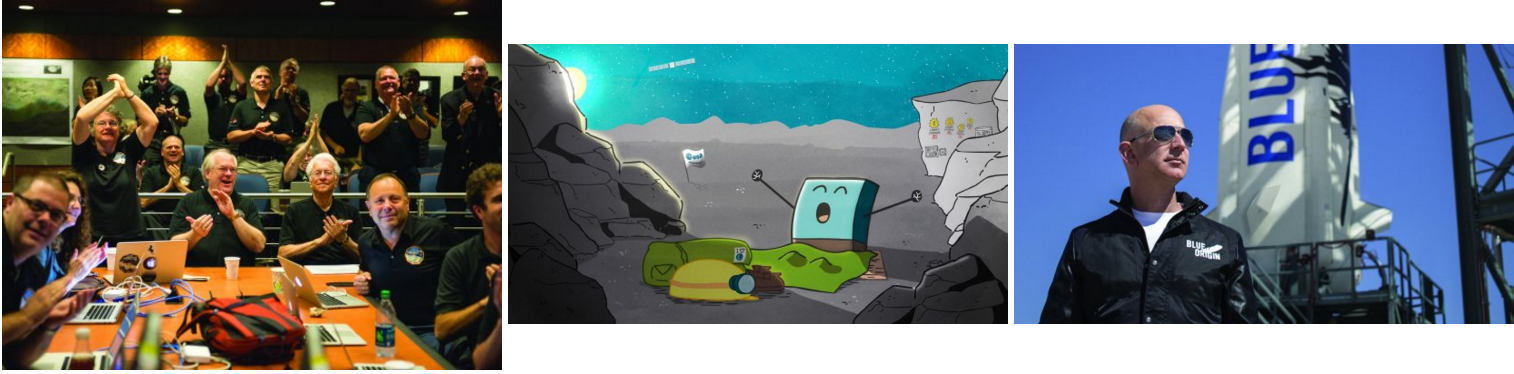

Thus, a good deal of aerospace communications EFT-1 test flight for the Orion programme takes off. This page (top): Scientists on NASA’s New Horizons team celebrate when the International Space Station (ISS). As Dartnell the spaceship flies by Pluto. (Bottom): An ESA scientist takes a photo of a model of the Philae lander, part of ESA Hadfield’s tweets from his six-month sojourn and the UKSA’s Rosetta mission is centred around education. Poster child for space communications, Commander Chris Hadfield, held classrooms in space – for all ages – in which he sent tweets, videos and photos beaming back to Earth from pointed out at a Social Media Week London event, he wasn’t playing around, he was doing real science. Hadfield’s audience was learning alongside his fellow astronauts and engineers.

aboard the ISS reinvigorated the social media fervor for space exploration. NASA, for one, has 500 Twitter feeds run by teams, individuals and organisation wide. When New Horizons flew past Pluto earlier this year, NASA previewed the first photo to stream back from the outer solar system on Instagram, before turning to traditional media an hour later. Social has become a key part of communications in the aerospace industry. For the UKSA and ESA, the communications around the Rosetta mission, the 10-year flight to send the Philae lander to a far-flung comet, made social a priority. Dartnell says Philae was given a personality, a bold move, but one that paid off as it made a complex mission accessible. The personification of the little robot was complemented by animations, graphics and a characteristic Twitter account.

For Philae or, to a lesser extent, the Mars Curiosity rover, social makes it easier for communicators to share content. As Jacobs says, “As communicators, we have to think about how we do our jobs differently in the 21st century. In the past, traditional media relations people would work with the media to get their story told. Today’s technology allows us to talk directly to the public and it comes at a time where traditional media simply are no longer covering us as in previous years. There are fewer dedicated space reporters and we need to find creative ways to reach the public. Social media platforms provide that vehicle.”

Marek Kukula, public astronomer at the Royal Observatory Greenwich – an institution with close ties to the history of astronomy and space exploration – says social media has changed how the sector communicates, “What social media allows you to do is to have that sense of communicating directly with the people who are actually doing it – the scientists and engineers behind the scenes or astronauts on the ISS. Rather than just a news story, you actually get a sense that they’re real people behind the project. That’s an important thing because we want to encourage young people to study science and engineering and then go on to study those in university and seeing real people doing that is a very powerful.”

Jacobs echoes, “I believe it helps bring NASA’s value into focus. Whether we’re talking about our journey to Mars or the International Space Station, we have multiple opportunities throughout the day to reach across multiple platforms and engage the public in specific examples of how we’re advancing knowledge, technology development, and working to create new generations of explorers.”

Kukula says working in education and awareness has allowed for a continued interest in space exploration. The Royal Museums Greenwich, of which the observatory is a part, has also found that linking space to art is a good way of reaching new audiences. The two mediums have always been closely linked – the Hubble’s brilliant photographs are only the most prominent example of this relationship – but integrated programmes can help. “Scientists like art as well,” he says.

A rough road leads to the stars, though. Simon Sheridan, ESA researcher for the Rosetta mission said on the Long View that the premature release onto social of images and incorrect information about the Philae lander caused a media relations problem when communications stopped being consistent.

The 21st century has also heralded in a new age of space exploration, that of the private company. Space is up for grabs and businesses are seeking it out. Space X is Elon Musk’s brainchild and Virgin Galactic, Richard Branson’s reach for the stars. Blue Origin, a private exploration and astronaut experience company run by Amazon’s Jeff Bezos offers a third perspective.

Jacobs says this is a natural development, "We now live in an age where commercial companies now engage in activities that were once the exclusive purview of individual countries. That’s incredible and NASA is proud of its role in helping to foster this new commercial space industry, so we’re always looking for opportunities to share their advancements.”

Space X may be more well-known due to its current role as a space freighter, but Blue Origin avers that it will uphold the mantel of the tradition of space exploration. Global brand consultancy Siegel+Gale rebranded the company. Siegel+Gale’s CEO Howard Belk says his team looked into Blue Origin’s story. Its proprietary rocket designs are created in the same tradition as the rocket-borne spacecraft of the last century but have the biggest windows of any private company’s design – thanks to modern technology.

Belk says, “What became apparent as we spoke with the people behind Blue Origin was an absolutely authentic passion for space exploration that was shared by the entire organisation. This is a group that feels honored to extend the legacy of NASA. And I think it’s clear from their website that they are appealing to a special customer that wants to be participate in something big – the continuing human adventure of space exploration and science and discovery. Part of the Blue Origin story is every one of those flights will be gathering information that can be used in labs to understand more about space.” The new brand is simple and based around the image of a single feather – flight distilled to its most basic concept, Belk says – and a subtle nod to Galileo’s legendary gravity experiments from the top of the Tower of Pisa.

Despite this focus on heritage, Siegel+Gale sought to avoid the clichés rife within aerospace. Swooshes and rockets abound. Mission patches at NASA have for years made fun of this and incorporated it into design. Lockheed Martin’s Skunk Works is a leading aeronautics innovation arm of the business represented by a cheerful little cartoon skunk.

“We now live in an age where commercial companies now engage in activities that were once the exclusive purview

of individual countries. That’s incredible and NASA is proud of its role in helping to foster this”

Yet, Belk says, branding must reflect credibility, authority and safety. It’s a high-risk sector and veteran companies like Pratt & Whitney and Sikorsky must use visual cues to ensure this message is communicated to potential buyers in government or defense. Belk adds, “The platforms commercial aviation brands are built on are reliability and safety and those things that matter not only in the products but how the products perform. Those are really important because literally lives are at stake. As soon as you get in an aircraft, if things go wrong, they go really wrong. Those kind of messages of technology innovation, engineering excellence, mission critical products, uncompromising standards of performance and things like that become central to the brand story.”

Aerospace is a massive industry with widespread, diverse audiences. But its impacts can be felt as far away as Pluto or as close as the Royal Observatory Greenwich. Social media has been the driving force in bringing the universe closer together and allowing the organisations in the sector to communicate more effectively. Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin did the unthinkable, they brought back a piece of space – literally and figuratively – from the moon. They proved to 600m people around the world that space exploration is achievable. Earth in 2015 is a vastly different place, but whether its through a rocket ship from a private company like Blue Origin, a groundbreaking test flight from a contractor like Lockheed Martin or a curious little rover on a distant comet or another planet, space is there, waiting for us. The race is on.

Mars is more or less what’s ‘next’ in near-space exploration. A few rovers have crashed into the planet and a couple more are merrily making their way about the fourth rock. The European Space Agency has a planned rover programme aiming for Mars in

Mars is more or less what’s ‘next’ in near-space exploration. A few rovers have crashed into the planet and a couple more are merrily making their way about the fourth rock. The European Space Agency has a planned rover programme aiming for Mars in