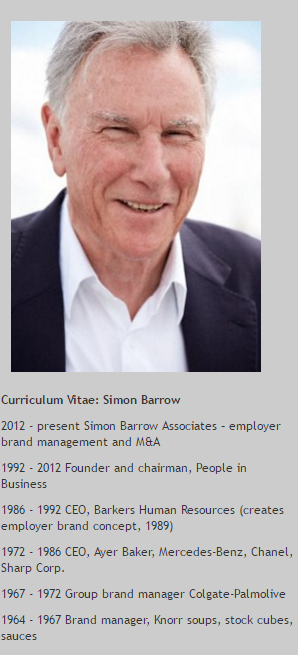

DEFINING A DISCIPLINE

Establishing the concept of employer brand management, Simon Barrow has defined the ideal relationships between employees and employers. Andrew Thomas talks strategy with the veteran communicator

Simon Barrow, the creator of the employer brand manager concept, doesn’t think his work has been in vain, despite the recent growth in job insecurity. “I’ve definitely seen progress since I first started. The big, good companies are behaving in a better way. The bad behaviour has always been from companies with a rotten entrepreneur, who runs out of cash, who cuts corners, or is just not competent enough to make the switch from a small business to a big one. Established big businesses know how to look after their people.”

He is still involved with the bad entrepreneur who wants to change their ways and the big company keen to make sure it is doing it right. These days, however, he also spends his time actively campaigning for more involvement from senior management in the employer brand process. He believes the employer brand management role should be a springboard for senior management as product brand management has long been. He has a unique perspective – before creating employer brand management, he ran the entire gamut of brand management positions; from product brand manager through to entrepreneur and boss of a large agency.

He is still involved with the bad entrepreneur who wants to change their ways and the big company keen to make sure it is doing it right. These days, however, he also spends his time actively campaigning for more involvement from senior management in the employer brand process. He believes the employer brand management role should be a springboard for senior management as product brand management has long been. He has a unique perspective – before creating employer brand management, he ran the entire gamut of brand management positions; from product brand manager through to entrepreneur and boss of a large agency.

His origins in the human capital business started, however, accountancy. Right at the outset of his career he took a summer job in New York, working with a Price Waterhouse team on cost control in a Brooklyn brewery. The project ended with a week of his contract still to run and the brewery management offered him five days in their ad agency on Madison Avenue – BBD&O – at the height of the Mad Men era. He left New York, eschewing brewing and accountancy. His ambitions were now firmly set on entering the marketing business.

Luck was on his side – he found the right role, and spent the next three years in the food business as a brand manager on Knorr (now owned by Unilever). This was followed by a stint as the brand manager for Colgate Fluoride. Barrow was happy with the way his career was progressing, and then, shortly after turning 32, Colgate asked him to join the global management team, with the added attraction of becoming general manager of the Benelux office.

Barrow says, “I thought, what does that mean? Do I want to be an international gypsy? Do I want to end up in New York? Most importantly, what were the chances of ending up on Colgate’s board? I checked. It’s changed now, but back then there wasn’t a single Brit.”

Barrow decided it was time to leave to leave Colgate, making a conscious decision to bring his brand management experience into advertising. He joined Charles Barker, a corporate and City communications group with a team of 700 people. It was a formidable presence in 1972, with a fledgling consumer ad agency that Barrow started to grow. Within four years he was made its CEO. The next 10 years were spent growing the business with accounts like Mercedes Benz, Chanel, M&G, and Sharp Corp. He put to use what he had learned from Colgate, but also continued his own personal development, “I learned a great deal about the communications business, about hiring, firing, developing, winning and promoting; all the things you do if you have to run a service business whose life blood is new business.”

Barrow needed to distance the consumer-facing work that his arm of the agency was producing from the more financially- oriented work from the rest of Charles Barker. He took part of the name of the company’s American partner, NW Ayer, to form Ayer Barker. NW Ayer was the oldest agency in America, and was behind some of the most globally recognised campaigns, from ‘A diamond is forever’ for De Beers to AT&T’s ‘Reach out and touch someone.’

According to Barrow this rebranding was crucial for the success of the agency, “It was my first, definitive, piece of corporate branding and it prompted my earliest employer brand thinking. The kind of folk I was looking to recruit came from the big name agencies: Y&R, JWT, Ogilvy etc., not from the world of the City. So Ayer Barker became the first time a decent consumer ad agency emerged from City roots.”

Ayer Barker was eventually sold to NW Ayer, and Barrow was moved across to another Charles Barker division, Barker Human Resources, the recruitment communications division of the group.

Barker Human Resources was a giant, an advertising factory creating over a 100,000 job ads per year and responsible for over 6m copies of what then were called house newspapers. Although profitable, Barrow found the role frustrating. “I thought it was reactive. Keys to success were following the client’s brief, expressing it powerfully but taking no risk, at an acceptable price with a quick turnaround. Where was the strategy in the world of work?”

Unable to turn away from his history of brand management he started to apply coherent thought to the work the agency was producing. “In 1989, I suddenly realised it was something else. It’s an employer brand. The same principles apply; good planning, good research, creativity, inspiration, coherent execution and good measurement. Those are the perennial bases for good brand management of anything.” Over the following year, Barrow further defined his employer brand management model and in 1990 he delivered a speech on what is now regarded as the unveiling of the employer brand concept.

Making reference to the young Procter & Gamble marketer who, in 1931, was credited with creating the concept of brand management, I asked Barrow if he thought this was a ‘Neil McElroy moment.’ It’s clear that McElroy is something of a hero to him.

Barrow says, “I’ve often thought, would that I could be like him. He was a remarkable man. He was a 26 year-old Harvard graduate working for Procter and he wrote a five-page memo (ignoring their one page rule) describing the idea and practice of brand management. By 44, he was Procter’s CEO. After World War II he became Eisenhower’s secretary of state for defense. He was a leader from the start.”

Barrow returns to the subject of McElroy later, when we are discussing whether employer brand management is able to attract the right calibre of people. He says, “There are a number of remarkable people, who enter the marketing and communications world and go on to do great things. P&G continues to produce star business leaders. Barrow wants employer brand management to attract similarly ambitious people. He says “A great function should be able to celebrate its own alumni.”

One of Barrow’s problems with marketing, communications or human resources having responsibility for employer brand management is that those departments are not always part of a company’s senior management. “Most people with the title employer brand manager, when you press them, are responsible for doing enough research to find something compelling to say about their business, but they are not in any way responsible for changing the business. My belief is you start employer brand management at the top. If senior management doesn’t want to get involved, walk away.”

The employer brand as an idea is known globally, but Barrow is fearful of complacency. “Brand management is in pretty good shape in what used to be called FMCG and in the B2B market. But in the world of work there is still much to be done. I felt that was the case in 1989 and I still feel that now.”

He points out that the need for great employer brand management remains intense, supported by Ipsos Mori’s Captains of Industry report from December 2015 which stated that finding and retaining the right staff were by far the most important issues facing companies today. He says, “An EB should be able to help create a real ‘one nation’ at work – a team driven by a worthwhile aim, shared values, trusted and respected by the leadership and vice versa. It should help overcome some of the current enemies of promise such as the vast income differences, short termism and the number of people who are not connected with the core team in the way full time employees should be.”

The largest problem, he says, are the forces of conservatism in HR and marketing and communications plus insufficient involvement from the top team. Employer brand management driven from the top, can change people management and a company’s reputation as an employer by making it a more coherent process with performance measurement studied by the senior team with the same intensity as financial and marketing numbers.

Barrow says it’s apparent when the CEO of an organisation has limited involvement in the employer branding by just a cursory look at that company’s career website. “Most of the material there is dead safe, dull and samey. In no way does it reflect any real point of difference. Ironically, that is true for great marketing companies whose career websites do not reflect their marketing principles. There is plenty of reality once you know the firm from the inside, but nobody dares to say how it really is so that is left to social media and hearsay.”

Echoing the current trend, Barrow feels that attachment towards a company is strongest from employees. “Of all stakeholders, the employee is emotionally the closest. In some ways they are family. They know a great deal about the business. They want to be proud of what they do and who they do it for and they want to be involved. Working for a company is part of a person’s life. It’s part of their identity. When a company doesn’t treat its people well,” says Barrow, quoting Arthur Miller, “That’s when they start not smiling back and that’s an earthquake.”

That emotion from employees, is, however, often cited as absent in the Millennial generation. Young employees seem to distance themselves from their employers far more than their antecedents. Barrow says the issues lie not with the employee or with the employer, but sadly exist as a sign of the times. “The Millennial generation doesn’t have a job in the way previous generations did. Zero-hour contracts mean they have to live by the hour, they have to work when they are needed. When many of today’s generation know that they can’t expect any permanence about what they do, why should they share an emotional relationship? It doesn’t mean they don’t want one,” he says, adding, wistfully, that he would love an employer brand conversation with Mike Ashleigh, the controversial CEO of the much-criticised Sports Direct.

Having created the employer brand management concept, Barrow has defined it further. Together with Tim Ambler, a fellow of the London Business School, he published the first academic paper in the Journal of Brand Management in 1996. By this time, Barrow was running People in Business, a consultancy practice he had launched under Barker Human Resources, and bought out in 1992. He sold it to an American firm in 2007, but remained its chairman until 2012 when he left to focus on the senior management driven work he does now.

The last four years have’t seen him quieten down, however. Supplementing his active advisory role, he is also active in the upcoming referendum on the UK’s EU membership. He’s keen to see employers stop hiding behind the ‘it’s political’ reason for not expressing a business view particularly on the subject of its impact on great talent. Despite nearly 50 years in business, Barrow has no intention of retiring. “I don’t quite put in the hours I used to as a young man,” he says, “But I think, without the excitement, challenge and innovation of ideas and seeing them happen, I’d be emotionally far poorer.”

Photographs by Jeff Leyshon