INFLUENCING THE INFLUENCERS

National politics is the purview of a select number of influential people. Yet, the public affairs and lobbying industry that supports its communications, campaigns and public relations is essential in the UK. Amy Sandys analyses how that industry has changed, thereby changing the nature of political influence itself

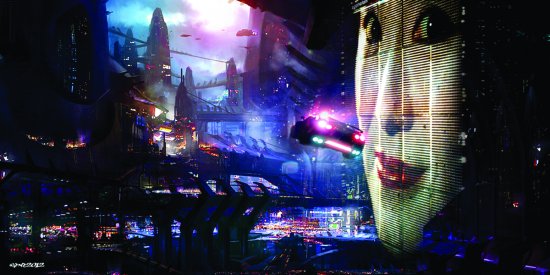

"Reagan's easy slippage between movies and reality is synechdochic for a political culture increasingly impervious to distinctions between fiction and history," says Michael Rogin, in his 1987 book, Ronald Reagan the Movie: And Other Episodes in Political Demonology. Rogin bases his comment on the less-than-illustrious film career the 40th U.S. president enjoyed before winning the presidency for the Republican Party in 1981.

The future of political communication, where hyperbole is commonplace and facts seem irrelevant in the face of spin, is remarkably reflected in Rogin's words.

However, the relevance of this foresight in current political communications in the UK is contested. The recent, unprecedented rise of Donald Trump has made it clear that election strategies in the U.S. are changing – it is no longer enough to rely on old party allegiances to ensure election. And, though the impact of such individualistic and personality-focused campaigning remains fairly unique to the U.S., certain similarities are beginning to arise within the UK circuit, too.

Public affairs and lobbying has an increasingly important role to play in the outcome of elections – and the rise of digital campaigning has certainly acted contrary to the UK’s, party-focused tradition. In some respects, however, culture and tradition are simply too strong to be swayed by the political machine.

The unitary nature of the UK versus the federal nature of the US is integral in forming election communication strategy. John Punter, associate director at public affairs specialist, the Whitehouse Consultancy, says, "We're very centralised, whereas America isn't, which means every federal state has its own voting rules which is not necessarily the case here. The other difference between our political culture and America is they broadly only have two parties. We have our two leading parties, and although it's very difficult to win a seat in Parliament due to the electoral system, it's not as difficult, necessarily, to win a council seat, because the margins of those can be 50 or 100 votes, and that's enough people you can meet in one day."

In the U.S., however, it is a different story. The effectiveness of election communications is tested by the sheer geographic area delegates must work with, and the high number of annual elections. This, to a large extent, has informed campaign strategy across the US, and can be attributed to the professionalisation

of digital services during election periods.

In terms of changing election strategy in the UK, Alex Singleton, head of media relations at non-profit business organisation London First, argues that it is, at least in part, down to the influence of the U.S. “We’ve copied, in the UK, some of what America does. Fifteen years ago, you could go to Washington DC and it would be so much bigger and more organised than in London.” And in the UK, no election communication strategy has undergone such vast changes in both importance and reach than digital communications. With the sector improving and updating year on year, the impact digital communications has made on election campaigning and political insight also has a traceable timescale. Lionel Zetter, managing director, Zetter’s Political Services and experienced lobbyist agrees. He says, “Five years ago it was a significant but not enormous part, and 10 years ago it barely featured.”

“If you’re looking to influence government, you know there’s a benefit in making sure you’re communicating to both sides – you’re not just influencing government, you’re influencing policy making as a whole”

Yet, Zetter argues, the singularity of digital communications ensures it remains only one aspect of an overall strategy to gain seats and votes. He says, “That channel of communication has changed but that’s all it is, it’s a channel of communication – although digital can be very targeted.” This increasing emphasis on digital has ramifications for the private sector’s role in election campaign communications. Technology can now allow political entities to engage with potentially influential stakeholders, and more traditional methods of communication are becoming redundant.

Carl Thomson, director of the Whitehouse Consultancy says, “There are companies and consultancies now rolling out campaign management technology, so data collection is becoming a very big part of running a campaign, maintaining mailing lists, etc. As digital and online campaigning becomes more important, as political campaigns become more sophisticated, in terms of the data collected on members and potential voters, there’s opportunities there for the private sector.”

This in turn has led to a more PR-driven campaign focus. Technical aspects remain integral in effectively communicating the party line, and ensuring strategies are in place to disseminate the message as widely as possible is imperative. Yet, campaigning is now more direct, reaching people across platforms such as Facebook and Twitter – in effect, into personal spaces. It must therefore be engaging, particularly if seeking to dissuade potential voters from public media narratives – and the message must be clear and impactful.

Zetter says, “During the 2015 general election campaign last year, the Tories spent a huge amount of money on Facebook. They spent a lot of money identifying people who fell into the demographic of people who were likely to vote for them or who were likely to be persuadable. Whereas, going back to the 80s and 90s, it was often all about giant poster campaigns and newspaper advertising – online and social media just gives campaigning a whole new dimension.”

A wider reach gives rise to a new plethora of external stakeholders. There is less flexibility in UK political campaigning as far as budgeting is concerned, but if influence is taken into account, the party still holds the whip. Singleton says, “In UK law, it’s very difficult for big companies to give money to political parties. If you’re a plc, you have to get shareholders to vote on donations to political parties, and the result is that the money doesn’t flow into political parties in the way that it does in the U.S. So inevitably it’s a much smaller, more reserved affair.”

And with such budgets imposed upon parliamentary candidates, which are then regulated by the electoral commission, fundraising is barely a factor of UK campaign strategty – in the U.S., it allows more targeted messages to be sent. Zetter says, “What Trump has found is you put a few messages out there, you find out which ones are achieving cut through, and then you just bang on remorselessly about them. You don’t allow yourself to be knocked off course or distracted or diverted. You just keep pushing that message. And that’s what worked with Trump to the point of getting the nomination.”

In the UK, the democratic process sees organisations sorted increasingly along ideological lines. Yet, Zetter argues that, as the centre ground inhabited by the two main parties for the previous 20 years becomes increasingly distinct, attendees to specific party conferences have once again reverted to type. Zetter says, “There is a very strong role for businesses in party conferences, but I think it’s changing back to where it was before – it’s mostly trade unions and charities at Labour conferences, and businesses and charities who go to the Conservatives. Charities tend to go for all three, but it’s sort of settled back into the original – there are not many businesses at a Labour conference, and there are not many trade unions for the Tories, and they’ve reverted to type.” In this instance, ideology comes into play perhaps more than pragmatism.

However, transcending party political boundaries is often imperative for organisations that rely on funding for future progression. The arts is one such area where being confined to a single party conference might be detrimental for its overall goals, despite unions which protect particular interests being affiliated to a specific party. Thomson suggests that for any organisation looking to have an impact on political decision makers, it is worthwhile communicating, as extensively as possible, across the party spectrum. Thomson says, “If you’re looking to influence government, you know there’s a benefit in making sure you’re communicating to both sides – you’re not just influencing government, you’re influencing policy making as a whole.” Indeed, the roles played by lobbyists or public affairs professionals can transcend political party boundaries – it is policy, rather than government, which is the intended target of influence.

Public affairs professionals with an interest in the specific ambition of an organisation, particularly charitable or arts-based, are likely to hail from across the government. Despite a recent, more divisive government paving the way for the increased division of organisations along party lines, approaching party politics as a singular organisation of influential individuals can be much more effective than remaining rigidly with a party of traditional association. Maddy Radcliff, campaigns and public affairs officer for trade union the Musicians Union (MU), says, “Luckily for us, music is widely supported. Some in politics look at music in purely economic terms, like the number of jobs the music industry supports and the money it brings in to the UK Treasury. Others look at it purely artistically – art for art’s sake.”

Yet for some unions, the uneasy relationship between the traditionally business-minded Conservative Party, and a Labour Party with shifting opinions on how much influence trade unions can exert, has caused the relationship between the two entities to become more complex than a B2B relationship. Like business, unions donate money to the party of their choice. However, unlike businesses, unions are almost unanimously affiliated to the left-leaning political parties. In this sense, the MU is no different, Radcliff says, “As a trade union, the MU’s job is to represent workers and the Labour Party is the party that historically represented working people.”

Ultimately, it is in an organisation’s best interest to ensure its communications strategy is flexible enough to use public affairs effectively. For some sectors there is a historic relationship between organisation and party politics. Yet, for others, the broader communications landscape is best approach with an open mind. As Radcliff says, “We have good relations with MPs across the main political parties and that enables us to get involved in important discussions about everything from arts funding and music education to licensing and copyright.”

As for public affairs, it seems unlikely for the UK to fall in line with the methods deployed across the US at any point soon. Punter says, “It’s important to appreciate that it’s not just the way politics works among the politicians, it’s the psychology and culture the country grows up with. Brits are used to our culture of it. Even though we’re both functional democracies, we function very differently.”

The distrust of public affairs in the US ensures it is more likely for voters to be swayed by individual rhetoric. In the UK, its centralised system and strict election campaign budgets mean that, even with the dominant role played by digital, party politics is always the focus. This paves the way for a more open engagement between stakeholders, and a more integrated system in which businesses, charities and political parties are less distinct from one another. It is this openness which ensures campaign communications are not based on what Rogin would describe as an ‘impervious’ distinction between fiction and history.