ON THE FUTURE OF SPECIES

The Natural History Museum has worked to change its brand positioning and, with the reopening of Hintze Hall, has big hopes for the future of conservation. Brittany Golob reports on communications strategy from South Kensington

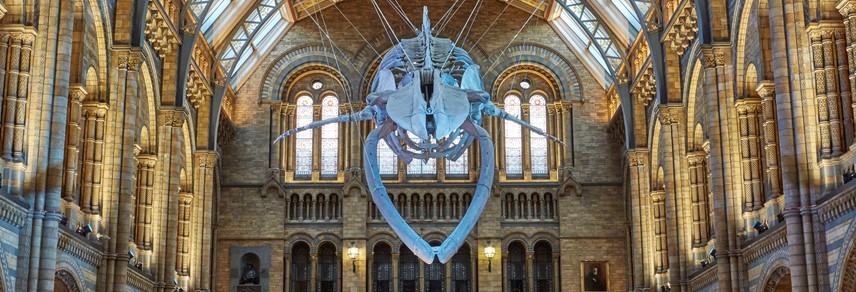

Walking into the reopened Hintze Hall at the Natural History Museum for the first time, it’s not just the incredible scale of Hope, the blue whale skeleton, that makes an impact. The sweeping staircase that leads crowds to other areas of the museum lies beneath the whale’s tail. The intricate details in the brickwork – including climbing monkeys and rams head plinths – are on show. The room’s many ‘wonder bays’ act as an index for the museum, giving visitors a preview of each of the museum’s areas of focus. But Hope is the star and visitors can look up at her from below or down at her massive skull from the hall’s balcony.

Hope is the result of seven years of planning, two years of implementation and six months of construction. She’s emblematic of conservation in action, of the impact humans have on the environment, of the value of science. She also represents a shift in the museum’s positioning, led by head of strategic communications Kate Fielding. The dinosaurs are still in place in South Kensington, as are the trilobites and petrified trees, but the Natural History Museum’s repositioning sees it become a bastion of hope for the future of the natural world.

Fielding’s objective over the past few years has been to change the way people perceive the museum. “People have this great affection for this place, and they really love it, but they see only a tiny bit of what we do.” She says shifting the perception from a children’s museum to an institution of scientific research and education has been the focus of the repositioning.

Two inspirational leaders in the scientific community galvanised the Natural History Museum’s internal audience to change. The first, was David Attenborough who said, “Nobody will want to protect what they don’t first care about, and nobody will care about what they haven’t experienced.” The second came from a moment at one of the museum’s annual trustee dinners when oceanographer Sylvia Earle said, “The next 10 years could be the most important in the next 10,000.”

The communications team also ran internal workshops to determine what the perceptions were, internally, and what they should be. Using the quotations as inspiration and compiling evidence from the workshops, Fielding went to work crafting a strategy. One of the major focal points was communicating in a post-truth society, she says, and the value of evidence-based policymaking. Eventually, working with the executive committee to refine the message, the strategy was formed around the words ‘ignite, challenge, empower and lead.’ Fielding says, “This is the journey from that first spark of curiosity and wonder of experiencing the natural world, through to learning more about the issues, the challenges and the science that lies behind it, through to some of the amazing work that’s being done by researchers here.” Hope becomes the representative for shifting the perception of the museum from being full of “dusty Victoriana,” as Fielding says, to a modern institution that is fighting for the future of the natural world, not just its past.

It’s a message that runs through not only the museum’s communications, but its actions as well. The new ‘Whales: Beneath the surface’ exhibit that launched alongside the reopening of Hintze Hall is curated along those lines. Visitors are drawn into the deep with artwork and film that submerges them in the world of cetaceans. Next, established understanding is challenged with an exploration of the evolution of whales and dolphins. Then modern science takes the lead as the animals’ anatomies and behaviours are explored and finally, new work carried out by the museum is used to pose questions about the next steps in the scientific study of cetaceans.

With a major exhibit and the Hintze Hall launch occurring on the same day, the focus could have been simply on those two events, though. Instead, they were used as an opportunity to put the new strategy into action, with the reopening acting as the centrepiece.

Making the launch a success, though, required years of hard work. Fielding says the media relations groundwork required media training for four main spokespeople and building relationships with the BBC, the FT Magazine and the Sunday Times, among other organisations. Getting coverage, Fielding says, was not the challenge. “It was about how are we going to get that core strategic message into the media outreach that we do and in the way people are talking about this across the media?” Ultimately, the work paid off and spokespeople as well as the rest of the museum’s staff began to talk about the museum’s purpose in the same way.

Building personal connections between visitors and the museum was also important. Fielding says, “That’s what we’ve really tried to push as well through the communications. Fundamentally we are a scientific institution, that means that people really like to talk about the areas of their own expertise and to be dealing in facts and evidence. As a museum we operate in a slightly different space, but [the challenge] was still having that scientific backing and pushing people to embrace slightly different ways of talking about what we’re doing.”

Social media too, offered a chance to engage. The digital content team created video and photographic content for various channels, including a film on the relocation of a 4.35m tall taxidermy giraffe into Hintze Hall. The team also worked with museums around the world on #MuseumWhales which saw institutions from LA to Berlin to Sydney welcome Hope to the global pod. The movement was representative of the collaborative global effort that finally put an end to whale hunting in the 20th century.

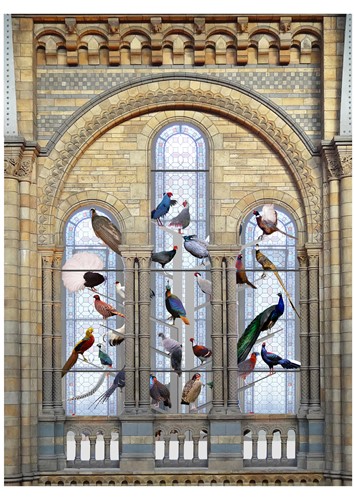

Blue whales were one of the major achievements in conservation in the last century. Their population had shrunk dramatically due to overhunting, but with a concerted, global effort to help the species thrive again, it is now recovering. By bringing Hope into the museum, she, and her cohorts throughout Hintze Hall – including the taxidermy giraffe, a mastodon skeleton, an art-like display of seaweed and a flock of seabirds – may inspire further efforts to respect, admire and protect the natural world.